How can I memorialize the lives of my Polish ancestors who died in the Holocaust? The generation of my Zaidy (grandfather) is gone. So too are their children, my mother and her two sisters. But I am trying to recover as much of their lives as possible. In this post, I record the search for my great aunt, my Zaidy’s sister, Chanche (Chana).

Chanche was her Yiddish name and the name by which she was probably known to her family. Her Hebrew name was Chana Golda. Chanche was my Zaidy’s eldest sister. She was one of six children who lived to adulthood born to my great grandparents, Chona (Elchanan) and Sheindl Wierzbowicz, all of whom were born in Zambrow. My grandfather, Yosef, was their eldest child, born in either 1899 or 1900. Chanche was their second child. Then came, to the best of my knowledge, Shmulke (Shmuel), Panche (Puah), Chaya Sara (Adele) and, finally, Hinde. Of the six, three of them, my Zaidy, Shmulke and Chaya Sara left Zambrow and made their way, at various times in the 1920s and 1930s, to the United States. The other three, may they be remembered, were murdered by the Germans.

I have attempted to piece together a picture, however sketchy, of Chanche’s life. I have relied primarily on three sources: family photographs, either sent to siblings in the United States or taken by Chaya Sara when she left Zambrow, documents obtained through JRI-Poland (Jewish Records Indexing), and a 1995 recorded oral history interview of Chaya Sara (to whom I will refer as Adele after she left Zambrow). The interview can be found on YouTube at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wTRgXGEA9-E.

Chanche was born in 1903. Her paternal grandmother, also named Chana, had died before Chona’s marriage to Sheindl in 1897. Chona named his first daughter after his mother.

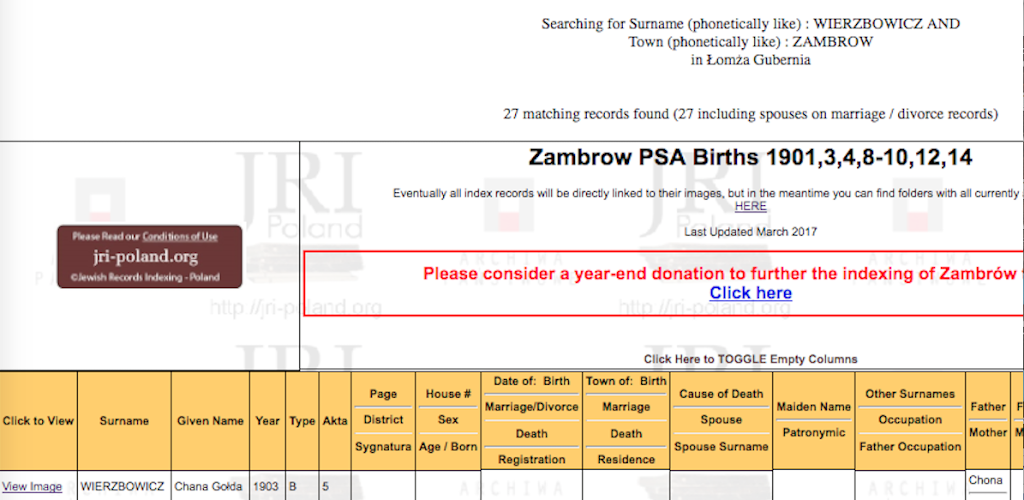

I learned this information by searching the JRI-Poland database. The search was made easier by the fact that Zambrow was a relatively small town, with a limited number of records, and that Wierzbowicz is an uncommon name.

Here is the result relating to Chanche when I searched for records of the Wierzbowicz family:

On closer inspection, however, Chana Golda was not the only child born to Chona and Sheindl Wierzbowicz in 1903:

The “B” in the “Type” stands for birth records. The “Akta” is the record number. This means that two children were born to my great grandparents in 1903, Chana Golda and “Kielman.” The record of Chanche’s birth is number 5; Kielman is number 6. Clicking on the “View Image” link reveals the following birth record, written, as were all records in eastern Poland when it was under Russian domination, in Russian Cyrillic script:

Through JewishGen’s ViewMate service (https://www.jewishgen.org/viewmate/), you can post foreign language documents and receive help from volunteers to translate them. I did so and obtained the essential information contained in this document. On January 16, 1903, Chona and Sheindl became the parents of twins, a girl who they named Chana Golda and a boy who they named Kelman.

I had never heard of Kelman before. What happened to him? The answer to this question is contained in the record that follows:

The “D” in record “Type” stands for death. Chanche’s brother Kelman died a year after he was born. His death, as sad as it must have been for my great grandparents, could not have been a shock. Although in Russia at the turn of the Twentieth Century infant mortality rates for Jews were half of that of the non Jewish population, 25% of Jewish babies did not survive their first five years of life. (https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/op236_mothering_medicine_ransel_1990.pdf) My Zaidy was four years old in 1904 when his little brother died, his first experience of death.

What follows, is a chronological sketch of Chanche’s life based on the limited information I have gathered. Here is the earliest photograph I have of Chanche:

Chanche sits in the middle between her younger brother, Shmulke, and sister, Chaya Sara. Chanche appears to be about 14 or 15 years old, and Chaya Sara, nine years her junior, about 5 to 6 years old. Chanche, holding a book in her hands, projects herself as confident, intelligent and mature young woman, dark-haired, attractive, with piercing eyes. She must have been a good big sister to Chaya Sara, whose physical closeness toward Chanche reflects a sense of tenderness and attachment. The photograph would have been taken around 1918, just after the conclusion of World War I, when life in Poland was returning to some semblance of normalcy.

Chanche was socially active and comfortable in social settings. In every photograph I have of her, she is with other people, and she is invariably seated in the middle, a center of attention. This photograph of Chanche as a young woman, surrounded perhaps by school friends and her teacher (left), reinforce the image of her as as a dynamic and strong-willed person. The youngsters are wearing some kind of uniform; perhaps she was part of a school production or club.

It is interesting to note that Chanche’s parents were both religious Jews. My grandparents’ home was kosher and the Sabbath and holidays strictly observed. Chanche’s father was reputedly quite learned in Gemera (the Talmud) and an excellent Chazan (cantor) who led services during Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur. Yet neither Chanche nor her friends appear very religious. The young men are not wearing kippot, though Chanche and her female friends are dressed modestly. By her late teens, Chanche was breaking free of her parent’s religious strictures, though, as we will see, she maintained her Jewish identity.

The next photograph of Chanche is of her and her mother, my great grandmother Sheindl.

Chanche looks to be about 20 years old. The two women don’t look too happy, as if something is weighing on them both. Perhaps they were worried about my grandfather, who’d recently left Zambrow. Or perhaps they were concerned about the political uncertainties facing Jews in the new Polish state. Whatever emotions they may be carrying, they appear to be occupying separate worlds. Though their arms are linked, there does not appear to be a strong emotional connection between them. Chanche looks straight into the camera, as if ready and resolved to face her future, whatever it may bring. Sheindl by contrast looks away, her emotions well hidden, perhaps suppressing the pains of the past and fears for the future.

In 1926, at the age of 23, Chanche married. Again, I learned this from JRI-Poland. (The “M” under the category “Type” means marriage.) The actual marriage registration certificate is not available, but the record does exist.

Chanche was married in Zambrow. All her family must have celebrated the occasion with her, with the exception for my grandfather, who had already left Zambrow. They never saw each other again.

According to Adele’s oral history, Chanche’s husband’s name was Max. Max is a name that modernized Jews in Poland sometimes used when their Hebrew names began with a מ (M sound). His name, which appears just above Chanche’s in the above document, appears as “Mortko,” which probably means that his Hebrew name was Mordechai. His last name was Tykocinski, pronounced Tykochinski.

Chanche and Max’s wedding ceremony must have been, by Zambrow standards, a lavish affair. The Tykocinskis were a prominent Zambrow family. Various members of the Tykocinski family are mentioned throughout the Zambrow Yizkor (memorial) book, including a reference to a Beinusz Tykocinski as the owner of the town’s cinema. The above JRI document, just below the 1926 Tykocinski-Weirzbowicz match, records the marriage of another Tykocinski (“Ick,” probably meaning Yitzchak), to Chaya Golombek; the Golombek’s were another important family in Zambrow. Max and Chanche would have known each other since childhood, though they were probably not classmates as Max appears to be several years older than Chanche.

Here is a photograph of Max from the Zambrow Yizkor book. He is seated second to the left in the front row. The book identifies the picture as a banquet of men of Zambrow, and judging by their appearance, they may well have been among the town’s elite Jewish citizens:

Whether or not Max was raised in a religious family, it appears he had become secularized by the time of his marriage to Chanche. Chanche’s parents were probably not too happy that their son-in-law was not religious, but they must have felt that Max was the kind of man who would be able to financially provide for their daughter.

By the time of her wedding, Chanche’s older brother, my Zaidy, was in Palestine. The following photograph, dated Passover 1923, shows him at a gathering in Tel Aviv along with other former Zambow natives:

My Zaidy is in the third row, second to the left, wearing a bow tie. This photograph is included in the Zambrow Yizkor (memorial) book, which identifies some of the other men. One of them (though it is unclear which man) is Noah Tykocinski, who was probably either Max’s brother or cousin. (Zambrow Memorial Book, p. 325.) I imagine that Chanche and her brother remained in touch by letter and that family news from Poland was exchanged between my grandfather and Noah Tykocinski.

Sometime after their marriage, Chanche and Max moved from Zambrow. I had heard from my mother that they moved to Gdansk, also known as Danzig. But that turns out not to be correct. According to Adele, they moved to a city whose name sounds like Gdansk, namely Grudziadz. Before the First World War, Grudziadz was part of Germany and known as Graudenz. It became incorporated into Poland and given its Polish name and spelling as a result of the Treaty of Versailles in 1919.

Though part of Poland, a sizeable percentage of its population was ethnic German. In 1921, Grudziandz had a population of 77,013, of whom 21,401 were ethnically German. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polish_Corridor#Ethnic_composition) It was not a particularly Jewish city, especially compared to Zambrow, where about half the population was Jewish. According to Wikopedia, only 600 Jews lived in Grudziandz by the time of the Nazi invasion in 1939. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grudzi%C4%85dz#Nazi_atrocities)

In the years that Chanche and Max lived in Grudziadz, the city “served as an important center of culture and education.” The city hosted a Polish military garrison and several military schools. “A large economic potential and the existence of important institutions like the Pomeranian Tax Office and the Pomeranian Chamber of Industry and Trade, helped Grudziadz become the economic capital of the Pomeranian Voivodeship (area) in the interwar period.” (Pomerania was the region in which Grudziadz was located). (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grudzi%C4%85dz#Interwar_years)

According to Adele, Chanche and Max created and ran a business in Grudziadz. They lived in a “furnished apartment” owned by a German woman, with whom they had an excellent relationship. It seems that Chanche and Max had created a comfortable life for themselves in Grudziadz.

Chanche and Max had two children, Solik and Shlomele (Shlomo). (I have been unable to locate their birth records.) Solik is a name of endearment for a child named Bezalel. Shlomo was Max’s father’s name (see marriage certificate, above; Max’s mother’s name is not recorded.) Since Ashkenazi Jews do not name their children after living relatives, Max’s father probably died after Solik was born and before Shlomo’s birth. Max and Chanche named their second son in memory of Max’s father.

There is only one photograph of the family, a blurry image of Chanche and Max, with Solik between them, and Chanche’s sister Chaya Sara (Adele). The picture depicts an urban setting such as might be found in Grudziadz:

Max appears as a distinguished, somewhat prosperous, gentleman. Neither he nor his son are wearing head covering, indicative of their modernist outlook. Chanche, now in her 30s, is a proud mother, well-kept, carrying a purse, still with that intense gaze. As in the first picture of the sisters, Chanche and Chaya Sara are physically close, the emotional bond between youngest and oldest sister still evident.

Solik, a spitting image of his father, looks like a fun loving and intelligent boy:

Here is the latest photograph I have of Chanche, taken in an informal setting, perhaps on vacation with her family:

I have not located any photographs of Chanche and Max’s other son, Shlomo.

There is, however, one more photograph of Chanche, and it gives additional insight into her interests and nature. I found it, unexpectedly, in the Yizkor (memorial) book of the town of Kolno. Kolno was a small town near Zambrow, and it was where Chanche’s father lived before he moved to Zambrow to marry her mother. I went to the YIVO archives in hopes of finding out more information about him or his family. I didn’t. But while examining the photographs, I came across this one:

There she is again, in front, in the middle, holding a banner, a member of a Zionist youth group called בני הגליל (B’nei Ha’Galil, or the Children of the Galilee), a branch of the Hashomar Ha’tzair. There is a misspelling in the caption of the group’s affiliation, with the Hebrew letter “ה” in place of a “ש.” The word הומר should read שומר.

The photograph is also misdated. It purports to be from 1932, which would have made Chanche 29 at the time, but she clearly looks younger than that. It is likely that it is from 1923, when Chanche was 20, three years before she married.

Shomer Ha’tzair was one of the most important Zionist youth groups in Poland, which emphasized self-reliance, outdoor life and scouting. It was an important influence on the founding of the kibbutz movement in Palestine. (http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/hashomer-hatzair) It was a secular nationalist organization, modernist and socialist in its outlook. This explains why, in the photograph, the men and women are interspersed. Chanche, as many other Polish Jewish youth in that era, had separated herself from the Orthodox lifestyle of her parents.

Chanche was an idealist, a Zionist, who dreamed of making a life in the Land of Israel. Maybe she gave up that dream after she married and had children. Or maybe she held onto it but of necessity deferred it owing to the necessities of making a living. Or perhaps she and Max wanted to make aliyah (immigrating to Palestine) but were unable to do so because, by the late 1920s and 1930s, the British were increasingly restricting Jewish immigration to Palestine.

After Hitler took power in 1933, life in Grudzaidz became more difficult for its Jews. Many of the ethnic Germans symapthized with Hitler’s ideas, including his anti-Semitism. This included Chanche and Max’s German landlord. At some point during the late 1930s, she told them, according to Adele, that they could no longer stay in the apartment because she feared for her own well-being. What happened after they left the apartment is unclear. Adele stated that they became essentially “fugitives,” traveling from town to town.

The Nazi’s invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, and Grudziadz was the site of a major battle as the Polish army futilely attempted to resist the invading Nazi forces. The battle ended on September 4, 1939, when the Nazi’s captured the city. The city’s ethnic Germans unsurprisingly welcomed the Nazi forces into the city, as this photograph of the Nazi entry into Grudziadz illustrates:

What happened to Chanche and her family? No one knows exactly. If, in the unlikely event, they still lived somewhere in Grudziadz, they probably shared the fate of the Jewish community there: arrest and transport “to an unknown destination [where] it is believed that they were most likely executed by the Germans in the Mniszek-Grupa forests.” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grudzi%C4%85dz#Nazi_atrocities) Or perhaps Chanche and Max returned to their native Zambrow and shared the fate of their family, shot at a mass grave or gassed at Treblinka or Auschwitz. Or perhaps they were caught up in the Nazi net somewhere else in Poland and the family members were shot, or sent to die in a concentration camp, or some combination of both. It is quite possible that Chanche and her family were killed before January, 1943, the final deportation of Zambrow’s Jews to Auschwitz. Perhaps her Zambrow family already knew that she was dead before they themselves were killed.

Chanche lived about, but no more than, 40 years. In my search for Chanche, she has come alive before my eyes, the image of a bright, energetic and caring woman. I would have liked to meet her and her family. Maybe I would have met her and her family in Israel. Or maybe she and her family would have joined her brother, my Zaidy, in New York. I wish I could have found out more about her from my grandfather and Adele. I content myself with this inadequate reconstruction of her life.

May the memory of Chana the daughter of Elchanan and Sheindl חנה בת אלחנן ושיינדל, Mordechai the son of Shlomo מרדכי בן שלומו, Bezalel the son of Mordechai and Chana בצלאל בן מרדכי וחנה and Shlomo the son of Mordechai and Chana שלומו בן מרדכי וחנה not be forgotten.